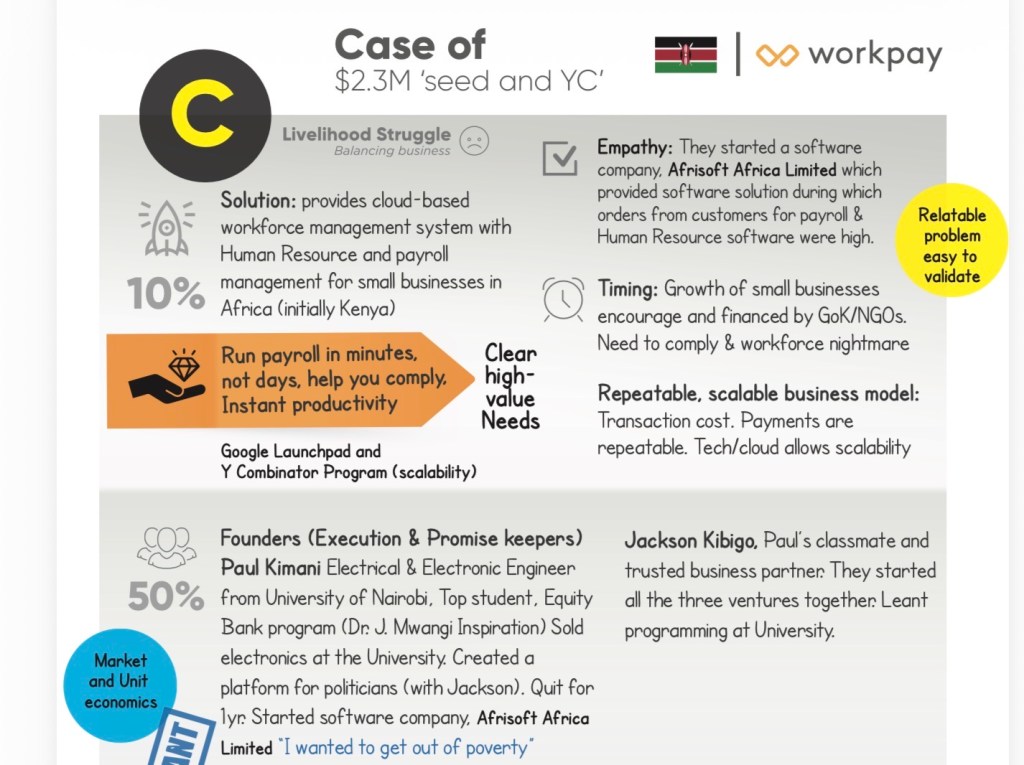

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) has been rapidly adopted across multiple sectors as firms seek to automate customer service, streamline operations, and provide real-time digital support. As global institutions such as the OECD emphasise, AI now functions as both an economic enabler and a governance challenge, requiring responsible deployment, human oversight, and contextual adaptation (OECD, 2025). This essay critically examines how generative AI is being used in business by analysing its integration within service workflows, its operational limitations, and its ethical implications. The case of Safaricom’s Zuri chatbot is used as a practical focal point to illustrate the challenges and opportunities facing businesses implementing AI-enabled customer service systems in Kenya.

Where AI Falls Short: Context, Human Language, and Escalation

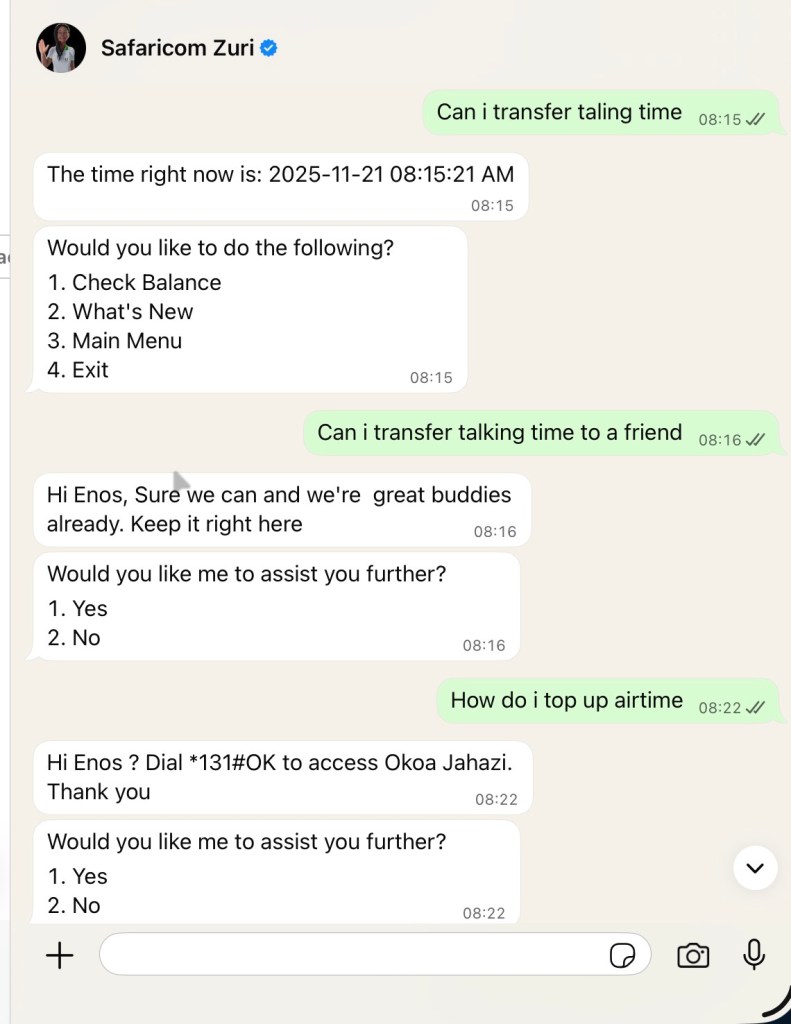

Safaricom’s Zuri chatbot is designed to automate common customer support tasks—including balance checks, PUK retrieval, bundle purchases, and menu-driven queries. In principle, this aligns with findings in the literature showing that chatbots are highly effective in tasks characterised by structure, repetition, and limited ambiguity (Dinath, Mashigo & Khumalo, 2025). However, my own interaction with Zuri highlights a much broader issue affecting rule-based and semi-automated chatbots. When asked a straightforward natural-language query—“Can I transfer talking time to a friend?”—Zuri repeatedly redirected me to an Okoa Jahazi service that was entirely unrelated to my question. This illustrates a widely documented problem in chatbot systems: difficulty recognising user intent when phrasing does not match predefined keywords or menu categories (Han, Du & Xu, 2025). Rather than engaging in contextual interpretation, the system loops through scripted responses, thereby creating user frustration and decreasing trust.

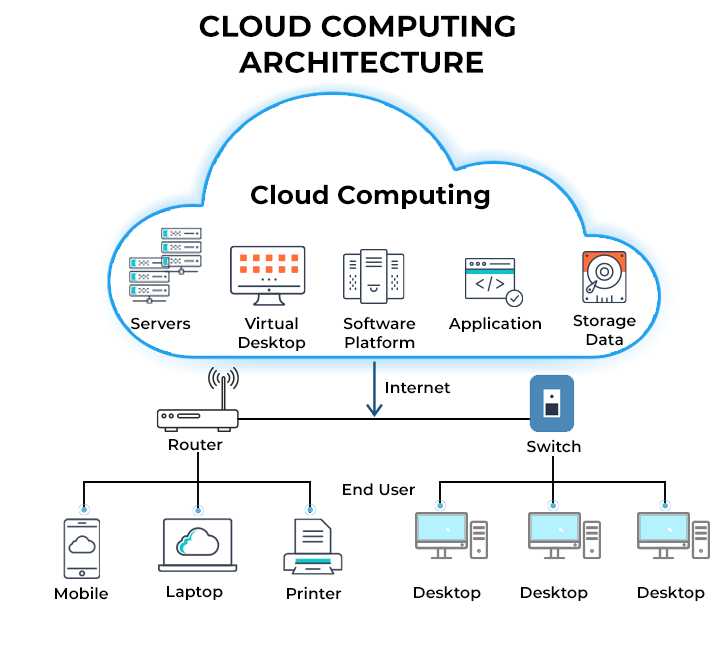

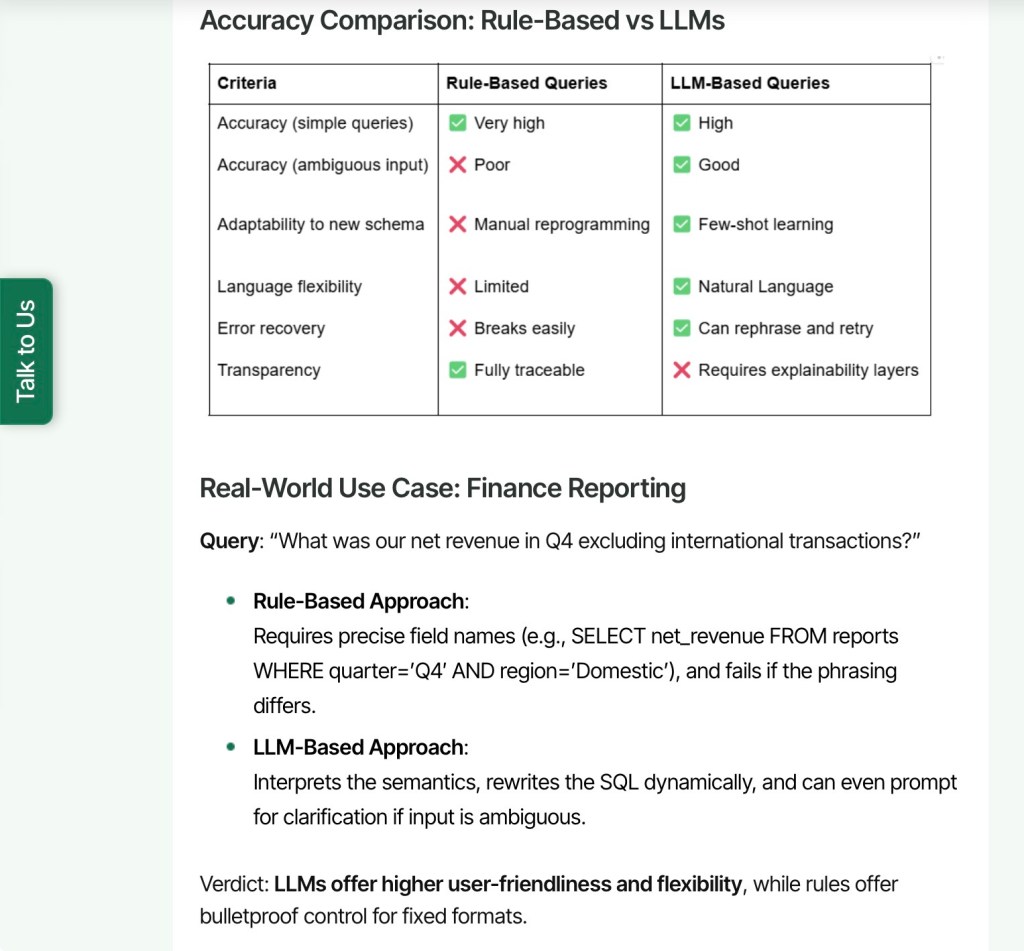

Understanding this failure requires clarity on the underlying technical model. Unlike advanced generative AI systems such as ChatGPT, which rely on large language models (LLMs) capable of interpreting free-form conversation, Zuri primarily employs a rule-based intent classification engine. Such engines follow fixed decision trees: if a user message contains a known keyword, the bot responds with a corresponding scripted action. As Dinath et al. (2025) show, rule-based chatbots exhibit near-perfect performance for structured queries but deteriorate significantly when handling multi-step or context-dependent tasks. In contrast, more advanced generative AI customer service engines—such as Google Dialogflow CX or IBM Watson Assistant—rely on natural language understanding (NLU) and dynamic intent matching, enabling them to infer meaning from varied phrasing and track context across multiple turns. The absence of such sophistication in Zuri explains both its mechanical responses and its failure to escalate unresolved queries to human agents, a flaw that further erodes trust (Glikson & Woolley, 2020).

Zuri in the context of AI design principles

Businesses typically integrate AI chatbots into their workflows through customer triage, transactional automation, knowledge retrieval, and analytics. In Safaricom’s case, Zuri is positioned as the first point of contact, intended to deflect high-volume requests from human call centre agents. This workflow is consistent with global patterns, where AI serves as the initial gatekeeper to reduce operational load (Tan et al., 2025). However, literature highlights that chatbot effectiveness requires two critical features: (1) contextual language adaptation, and (2) seamless hand-off to human agents (Følstad & Taylor, 2021). Kenya’s AI Strategy 2025–2030 similarly stresses the need to develop models grounded in local languages and user behaviour (Government of Kenya, 2023), while the UK National AI Strategy places strong emphasis on human–AI complementarity rather than substitution (UK Government, 2024). Zuri’s shortcomings illustrate what happens when these design principles are not adequately embedded in practice.

Towards Ethical, Human-Centred AI Systems

If businesses want AI to deliver value ethically and sustainably, a new design philosophy is needed. Evidence from both academia and consumer feedback suggests four ethical pillars:

1. Accuracy First: AI must be continually retrained with real Kenyan language patterns—Sheng, Swahili-mix, informal phrasing—not textbook English. Without this, intent recognition will always misfire (Dinath et al., 2025).

2. Human Escalation Must Be Built-In: Studies show that hybrid models—AI + human agents—produce the highest satisfaction levels and reduce abandonment rates (Følstad & Taylor, 2021). A “talk to human” button is not optional; it is ethical design.

3. Transparency and Agency: Users should always know they are talking to a bot and should not be forced through loops. Ethical AI respects user autonomy (Glikson & Woolley, 2020).

4. Contextual Performance Evaluation: Businesses must routinely analyse where AI excels (e.g., self‐service) and where humans must lead (e.g., emotional or high-risk cases) (Tan et al., 2025).

Despite these failures, it is important to acknowledge that AI can perform exceptionally well in structured domains. For example, Safaricom’s AI-powered agricultural chatbot for potato farmers, recently reported in Business Daily, demonstrates strong performance due to its reliance on predictable agronomic workflows and structured data inputs. This contrast underscores a key point from the OECD (2025): AI excels where tasks are routine and data-rich, but struggles where interactions require human nuance, empathy, or flexible reasoning.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Zuri’s limitations are not isolated defects but reflect broader challenges associated with deploying rule-based AI in complex customer environments. While generative AI holds substantial potential for transforming business workflows, its successful implementation requires contextual language training, robust escalation mechanisms, human oversight, and alignment with national and international AI governance principles. Zuri therefore represents not merely a “lesson” but a cautionary illustration of the cost—both financial and reputational—of deploying under-equipped AI systems in high-stakes customer-facing scenarios. Businesses seeking to integrate generative AI must balance efficiency with trust, automation with empathy, and innovation with responsible governance.

References

- OECD (2025). Governing with Artificial Intelligence. OECD Publishing. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/06/governing-with-artificial-intelligence_398fa287/full-report.html [Accessed 21 Nov. 2025].

- Government of Kenya (2025). Kenya Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2025-2030. Ministry of ICT & Digital Economy, Nairobi. Available at: https://ict.go.ke/sites/default/files/2025-03/Kenya%20AI%20Strategy%202025%20-%202030.pdf [Accessed 21 Nov. 2025].

- UK Government (2024). National AI Strategy – PDF version. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy / DCMS. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/614db4d1e90e077a2cbdf3c4/National_AI_Strategy_-_PDF_version.pdf [Accessed 21 Nov. 2025].

- Han, Z., Du, G. & Xu, M., 2025. Consumer Service Agent and Patient Adoption Intention: Recommendations From Chatbot or Human. Journal of Global Information Management, 33(1), pp.1–24.

- Dinath, W., Mashigo, T.B. & Khumalo, S., 2025. Evaluating the Effectiveness of a Rule-Based WhatsApp Chatbot in Automated Query Resolution. Proceedings of the 20th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, pp.208–216.

- Tan, R., Li, Y., Huang, Q. & Liu, H., 2025. Enhancing Customer Service Chatbot Effectiveness: The Effect of Dyadic Communication Traits on Customer Purchase Intention. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 26(3), pp.799–831.